Juneteenth

and the Premise of a Promise -

Rodney Coates

In 5 days, we shall celebrate yet another Juneteenth

here in America. This is a celebration

of what many consider the end of slavery for Blacks in this country. Two and a half years after the signing of the

Emancipation Proclamation, this celebration was accomplished as federal troops

arrived in Galveston, Texas, in 1865.

But as with all historical events, this one is filled with ironies and

paradoxes, hopes dashed and dreams unfulfilled.

This event, to many, represents the duplicity of power, the cruelty of

complacency, and the willingness of many to forestall, deny and ignore the plight

of the enslaved person. Consequently, as

I will argue in this talk, the so-called freedom of the enslaved person was a

check that continually has come back -marked insufficient funds, they were

offered the premise of a promise yet unfulfilled.

Let

me begin.

The first question is why the news of freedom took two

and a half years to come to Texas. Some

argue that it was deliberately delayed placating angry slaveholders still in

denial. Others say that the federal

troops waited for the order to give the enslavers one last chance to get the

cotton harvest. But then, we must also

understand that the war, our bloodiest ever fought, had nothing to do with

slavery and everything to do with power.

The enslaved were just another set of pawns in this political gambit as our

nation's leaders, North and South, battled to see whose version of America

would prevail—one controlled by Northern Industrial Elite and the other

controlled by Southern Plantation Elite. There was no concern about whether the enslaved

would be free, as acknowledged by Abraham Lincoln:

My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to

Liberia, -- to their own native land. But a moment's reflection would convince me,

that whatever of high hope, (as I think there is) there may be in this, in the

long run, its sudden execution is impossible. If

they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten

days; and there are not surplus shipping and surplus money enough in the world

to carry them there in many times ten days. What then? Free them all, and keep them among us as

underlings? Is it quite certain that

this betters their condition? I think I

would not hold one in slavery, at any rate; yet the point is not clear enough

for me to denounce people upon. What

next? Free them, and make them

politically and socially, our equals? My

own feelings will not admit of this; and if mine would, we well know that those

of the great mass of White people will not. October 16, 1854: Speech at Peoria, Illinois

Ultimately Lincoln did what was expedient to force the

rebellious slaveholding states back into the Union; he freed those enslaved

people only in the states in rebellion.

That is, he released those enslaved people he had no control over. No enslaved people were freed from those

states loyal to the Union and not in rebellion.

And so, the Emancipation Proclamation held out the premise of the

promise of freedom. A premise that never

came to pass as the "great mass of White people" refused to allow it

to come into being. The premise -that

All Men (humans) are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain

inalienable rights. The least of these

rights being "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness," which

constituted the premise that the Emancipation Proclamation promised would go

unfulfilled, a check written and returned marked insufficient funds. And it is this check that constitutes the

paradox of American justice that yet goes unfilled. But how did we get to this American paradox?

The

American Paradox of Race – The Freedman's Dedication to Freedom

The civil war ended on April 9, 1865,

as Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate troops to General Ulysses S. Grant

at the Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia. Thus ending the costliest

domestic wars America has ever fought as an estimated 1.56 million Union and

800,000 Confederates forces battled for supremacy. At the close of the war, some 4 million Blacks

(constituting 88% of all Blacks) were now free, but another 250,000 in Texas languished

in slavery. Neither Lincoln nor

Washington had any real impact on Texas, primarily because there were not

enough Union troops to enforce the order. Such force was not available

until after the surrender of General Lee in April of 1865, and General

Granger's regiment arrived two months later. Listen as

Granger declares their freedom in his General Order Number 3 was:

The people of Texas were

informed that all enslaved people were free following a Proclamation from the

Executive of the United States. This involves an absolute equality of

rights and rights of property between former enslavers and enslaved people, and

the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer

and hired laborer.

The freedmen are

advised to remain quietly at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be

allowed to collect at military posts, and that they will not be supported in

idleness either there or elsewhere.

I cannot help but wonder if any Whites

were advised to "remain quietly at their present homes, and work for wages

. . . and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

"Never in the history of this

country was such a restriction or expectation placed on Whites. As we

will see later, these were the seeds through which the infamous Jim Crow codes

and laws would ensue. But for now, let

us consider the response of the formerly enslaved person.

The responses of the formerly

enslaved people ranged from shock to exaltation, from acts of retribution to

praise, and from prayers and celebration to cries of despair and loss.

Some left not only the plantation but the South, seeking to reestablish

connections with family and communities broken and shattered as a consequence

of slavery. Others stayed to attempt to take on freedom where they were enslaved.

Regardless, these enslaved people challenged America to recognize their

equality as they sought to establish themselves as free people within America.

Ironically one of the first things

these free people sought to do was to embrace education. It should be

recalled that under slavery, it was illegal in many states to teach any Blacks

-either free or enslaved - reading and writing. But, even under slavery, Blacks

facing severe punishment still found ways to support and encourage

education. Therefore it is not strange that after the war and

Emancipation, the now freedman gathered in homes, cellars, sheds,

meetinghouses, and even under the shade tree in the fields where they worked

the crops to learn. They learned from

each other, teachers, clergy, or older family members. They not only learned to read and write, but

they retained their history as a people. Imagine the scene recorded

from South Carolina, as a six-year-old girl sits beside her mother, grandmother,

and great-grandmother (over 75 years old), all-embracing learning and reading

for the first time. From the beginning,

many of the freedmen distrusted the scalawags and, carpetbaggers and former masters,

demanded to learn to read for themselves, to learn math, and to read the Bible

firsthand. They established their schools -freedom schools to accomplish

this. These freedom schools were sometimes

funded by White aid and benevolent societies from the North, such as the

American Missionary Association and the National Freedmen's Relief Association,

Sabbath schools, and night schools. But most of the monies to fund these

schools came from the newly freed Americans, who privately sponsored their

schools.

One example of these churches/schools

is in In Sharpsburg, Maryland, and a small church known as Tolson's Chapel. Tolson's

Chapel was built by blacks just two years after the end of slavery in 1864. For

over thirty years, between 1868-1899, this one-room building was a church and

school near the Civil War Battle of Antietam.

The history of the schools housed in Tolson's Chapel illustrates how

African Americans across the former slaveholding states created and sustained

schools during Reconstruction. Here the

dreams of freedom were born as local Blacks sought to educate themselves and

their children.

Consequently, as

African Americans established their schools and advocated public education,

they claimed education as a basic right as citizens. This dedication of

the former enslaved to education laid the foundation for publicly funded

schools for Blacks and Whites throughout the South and border states.

These newly freed Americans sought

to become economically independent and exercise their full civil and political

rights along with the right to education. One of these efforts' most

significant outcomes was the establishment of all-Black towns across

America. These Freedmen's Towns, or All-Black towns, were established by

or for a predominantly African-American population. Many were founded by

formerly enslaved people and existed in many of the former Southern

states. For example, before the end of segregation, Oklahoma boasted

dozens of these communities, while in Texas, some 357 freedom colonies have

been verified and located.

For a brief period, the promise of

freedom flourished as Congress passed, then slowly, the States ratified the

so-called Reconstruction Amendments. These three amendments, the 13th,

14th, and 15th, abolished slavery and attempted to

guarantee equal protection of the laws and the right to vote.

So briefly, the illusion of freedom existed as the 13th

Amendment prohibited involuntary servitude.

The principle of citizenship was ratified with the 14th Amendment for

all born or naturalized and granted the right to vote and decide who could hold

office. These rights were again

reinforced with the 14th Amendment, which established that full

citizenship rights could not be abridged due to race, color, or previous

condition of servitude. Of interest is

that all debts of those associated with either the insurrection or rebellion

against the United States and even the claim for the loss or Emancipation of enslaved

people were considered unenforceable, and all claims shall be held illegal and

void. The problems were apparent as the Constitution denied women

the right to vote for the first time. Unfortunately, these amendments did not provide

any enforcement provisions nor preclude the former states or its members from

seeking to nullify, negate, or circumvent the laws.

No sooner than these

amendments were ratified, and after the assassination of Lincoln, state laws

and federal court decisions began to erode and nullify much of these throughout

the late 18th century. Many states passed what would be known

as the Jim Crow laws that limited the rights of African-Americans. And

decisions made by the Supreme Court, such as the Slaughter-House Cases in 1873,

undermined and prevented several guaranteed rights unenforceable by holding

that these privileges or immunities could not be extended to rights under state

law, and the Plessy v. Ferguson case in 1896, which established "separate

but equal" and gave federal approval to all the Jim Crow laws. These

rights would not be guaranteed until the Brown V. Board decision in 1954, the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The responses of Southern Whites to

the newly freed persons were not limited to Legislative or Court actions.

Responses by Whites

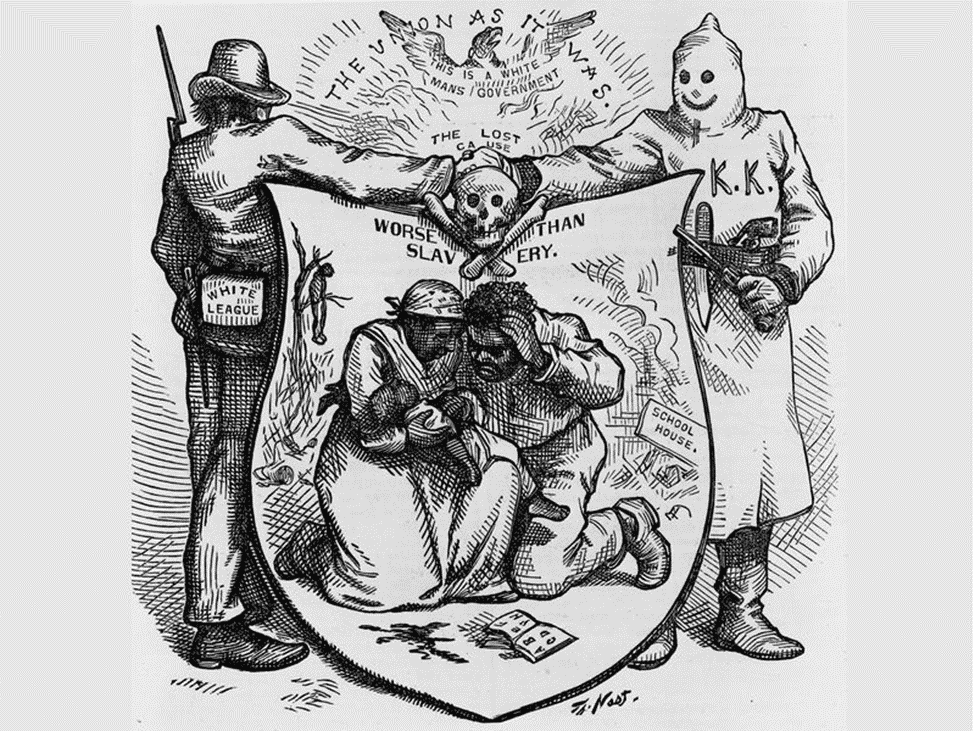

A cartoon

by illustrator Thomas Nast shows a member of the White League and a member of

the Ku Klux Klan joining hands over a terrorized Black family. (Library of Congress)

As the

American Blacks celebrated their new freedom, many Whites in the South mourned

the passage of what they believed was "their greatness." For

many Southern Whites, this was personal and represented a communal defeat,

marking the demise of the White Man and a time of dismay. They mourned

the loss of traditions, customs, families, property, and a whole way of life built

with Blacks' blood, sacrifices, and lives. Many considered leaving, while

others began to retreat into nostalgia and fictitious memories of the Old South

and mourning the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. The first

Confederate memorial associations started appearing in 1865 and 1866 as they

built cemeteries and monuments throughout the region. Others created

groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan, which resorted to violence, murder, and

terror to oppose this new freedom. The story of Tulsa and Black

Wall Street, and hundreds of other Black colonies, illustrates the terror that

ensued as the Africans sought to create their freedom.

No sooner than the 13th,

14, and 15th Amendments were enacted - which provided legal and

civil protections to formerly enslaved people - Members of the Ku Klux Klan

began systematic terrorist attacks against Black citizens for exercising their

right to vote, running for office, and serving on juries. Congress quickly

responded by passing a series of Enforcement acts of 1870 and 1871 which

attempted to end such violence and empower the president to use military force

to protect African Americans. The Act of 1870, for example, even

prohibited groups of people from banding together "or to go in disguise

upon the public highways, or the premises of another '' to violate another's

constitutional rights. Legislative intent aside, these acts did nothing

to diminish the harassment of Black voters across the South. Seeing the

lack of enforcement, the Senate passed two more Force acts, one known as the Ku

Klux Klan Act, designated to enforce the 14th Amendment and the

Civil Rights Act of 1866. A second Force Act passed in 1871 aimed to

place national elections under the federal government's control and empower

federal judges and U.S. marshals to supervise local elections. Then the Third Force Act of April 1871 gave

the president the power to use the armed forces to combat those who conspired

to deny equal protection of the laws and to suspend habeas corpus, when

necessary, to enforce the act. These acts temporarily assisted in ending

the violence and intimidation, but the formal end of Reconstruction in 1877

opened the floodgates for the disfranchisement and violence targeting African

Americans. Absent these protections and the insurance of the Jim Crow

Laws throughout the South – it was essentially open season.

Lynching became the most

frequent weapon to terrorize Blacks and force them into submission. By 1877,

lynchings were so normalized that they were flagrantly committed as public

displays. People dressed up invited friends and neighbors, and advertised

in local newspapers. Large crowds, whole families, would show up to watch

Blacks get their "justice" All too often, Blacks were punished

for being prominent, free, and successful. Many Whites -rich and poor -

used these to keep the Blacks in their place. Often the myth of the Black

man as a sexual predator was used to fire up the masses. All too often, the real insult was that

African Americans were perceived as being political and economic threats, not

sexual predators who wanted to foster integration to assault innocent White

women. Lynching and white riots were used to teach them a lesson, put them

in their place, and serve as a warning to any other Black arrogant enough to

challenge White supremacy. From the

late 19th century to the middle of the 20th century,

close to 5,000 Blacks were lynched. In Mississippi alone, some 500 Blacks

were lynched from 1800 to 1955. Lynching was not restricted to the South,

as over 35 people died in Ohio from lynching from 18972 to 1932. Few were

innocent, as a full range of Whites - from journalists to legislators, from

police to judges, from labor leaders to clergy -were anything but innocent

bystanders.

But Blacks were not content to

sit by and be lynched, as Blacks voted with their feet and initiated the largest

domestic migration movement in modern history as millions of Black relocated

from the most violent Southern regions to what was presumed to be a more

tolerant North.

But the White mob was not content to

lynch single individuals; soon, whole towns were annihilated.

Over the last few weeks, America has

become absorbed and shocked by the massacres in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921.

But we should point out that Tulsa was just one of at least 50 separate events

where African Americans were violently expelled from their homes, towns, cities,

and counties within the United States - most of these occurring from just after

the Civil War until 1954. To date, few have been brought to trial, even

though photos by the tens of thousands still can be found throughout the

internet. Never has domestic terrorism, public murders, and riots been so

celebrated.

And, of course, even as lynching and

wholescale black massacres began to wane, the Black church continued to be a

central target of America's racial angst. And herein lies an irony, during the whole of

the 19th century, only one church -the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal

Church in Charleston, South Carolina was burned down in 1822. Over the

next few decades and into the 20th century, an average of 6 churches were

burned each decade. Then we hit the end of the 20th century, where over 30

black churches were burned in just 18 months between 1995 and

1996. Congress finally passed the 1996 Church Arson Prevention Act. Clinton established a Presidential Commission

to document the burning of Black Churches, and they reported as many as 827

Churches might have been burned. But the spate of church burnings had not

ended; from then to 2018, another 16 black churches were burned. Last year

7 Black churches were targeted. These

attacks were attacks aimed at the spiritual core of The African American

Community. They sought to kill that spirit, but what they did was fire up

the community. Resounding calls could be heard as Blacks said Hell Naw, we

aren't going to run.

And what of the costs of all this

violence? During the period of slavery in the United States. If enslaved people had been reimbursed for

their time in forced servitude, it would have been estimated to range from

$18.6 trillion to $6.2 quadrillion. (compounded annually from 3% to 6%), And

another $35 trillion to $16 quadrillion for loss of land and property.

Finally, no one has calculated the cost of pain and suffering over these 400+

years, but again it would be in the quadrillions. This has been the cost

of White violence perpetrated against Blacks.

Where do we go from here? We start with a new premise and

articulate a new set of promises.

Toward

a new premise and promise

Even as I

write this, I know the triple threats Blacks face. These threats

-curtailment and suppression of voting, police, racially motivated violence and

attacks on Black Churches, and attempts

to shut down critical race theory. As we examine these threats, we

recognize that they are not isolated but represent a systemic attack upon the

Black community across America. Throughout

American history, whenever the nation has been confronted with an existential

threat, it has targeted racial groups, particularly blacks. This targeting has taken multiple forms of

personal attacks to mob violence, from lynching to massacres, but of late,

these have been institutionalized as the state has become the instrument of

violence. Hence, we note the mass

incarceration of black, particularly black males, and the war on drugs. We report the militarization of the police

and the over-policing of our neighborhoods.

We note the harsher sentencing and racialized use of the death

penalty. We note the increasing

likelihood of black children being expelled from schools, our churches bombed,

and our livelihoods continually threatened.

These continual assaults have increased psychological trauma, mental

health, and life expectancies. Blacks,

however, have not responded as victims but as victors as each generation has

fought to regain what was lost, reignite the fire of freedom, and walk with

dignity, head held high. As we celebrate

another Juneteenth, we celebrate this spirit of victory even as we acknowledge

the tragedies that continually beset us.

The current attack on

voter rights has a long and tortuous history, dating back to 1865.

We have been down this road before, where in the name of freedom and democracy,

many states with heavy black voters developed a system of checks to restore our

faith. Strange, none of these on the surface were racist. All of

them made sense until they were applied. And that application, not

particularly the laws, resulted in the wholesale suppression of the Black

vote. A suppression that lasted some 100 years, from the Voters rights

act of 1865 to the Voters rights act of 1965. And here we are

again. States across America are debating and passing legislation

that aims to install the 1776 project and reject the 1619 project. The

argument that Critical Race Theory is a racial attack on whites is absurd and

dangerous. Critical race theory does not blame current Whites for

what happened in the past, but it does point out the pain currently being

delivered by that past. It challenges much of our historical accounts

that belie historical realities. It helps balance the scales by telling

all of the stories of our history, not just the ones we feel comfortable

about. It means these stories from the vantage point of those that were

victimized. Imagine the story of rape or

incest or any other crime. Now imagine that we only hear the side of the

rapist or perpetrator and not the victim. Critical Race Theory recognizes

that the more sides of the stories we tell, the more balanced the histories

will be. And finally, the problem with

police violence is not a problem with the police but the police system.

That is to say; policing has been militarized to the point where our guardians

have become warriors.

As a consequence,

police go to war daily. As a veteran, I can only imagine what

it's like to be involved in a never-ending battle. This is a war with

no clear lines between us and them, between combatant and defender.

Perhaps, it's time that we declare a truce and rethink the purpose of

policing. In the process, we might decide that the problem is not the police

and courts but our schools and training. The issue is not bad kids but

bad opportunities. Let's help to create hope and better opportunities by

increasing the success rates in our schools and life chances. We might

see that we need less police. And in those situations where we do need

police, maybe they need to be accompanied by drug and family counselors, social

workers, and psychologists.

Dealing with

these threats will define the current struggle for justice and equality

originally promised on Juneteenth. And

we have a long history of dealing with existential threats and sustaining our fight

for justice and equality. Here let us remember that struggle and the

reality of our self-declared freedom.

In

1775, English scholar Samuel Johnson wrote, "How is it that we hear the

loudest yelps for liberty among . . .Negros?" The first antislavery

societies were founded the same year the Declaration of Independence was

penned. And while some debated the compensation that slaveholders should

receive, many argued for payment for the enslaved. When asked about the Emancipation of the

enslaved person, William Lloyd Garrison remarked that Emancipation was not

enough; we must be free from the caprice of man's cruelty to man.

Frederick Douglass that the Negro must own their solves and their futures; they

must have universal, equal rights and liberty. In an 1837 letter,

Angelina Grimke remarked that the freedom of blacks was a human and moral right

that could not be denied. Black history is American history; Black

liberation is the essence of American liberation. Until all realize the

promises of the Declaration of Independence, of life, liberty, and the pursuit

of happiness – none will experience these promises.

Although victimized

repeatedly, we have not succumbed to becoming victims. We have been and

continue to be overcomers. We have rebuilt what has been destroyed and relocated

where we have not been wanted. What we

have not done is abandoned our quest to breathe free. Nor have we failed

to achieve in every field of human endeavor -we have served in every war since

the revolutionary war with courage; we have built and continually rebuilt our

homes, communities, and lives. And what of these accomplishments, under

duress? Mathew Henson and Admiral Robert Peary explored the North Pole in

1909; Jesse Owens demonstrated to Hitler what a black man could do by winning

four gold medals in the Berlin Olympics of 1936. Jackie Robinson became

the first Black to enter the major leagues in 1947, even while blacks played

the sport for over 60 years. We have

Althea Gibson, Venus Williams, Coco Gauff, and Naomi Osaka, who might be the world's best

tennis player. With pen and prose, Gwendolyn Brooks won the

Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1950.

We have this amazing

young poet, Amanda Gorman, the youngest inaugural poet in U.S. history, an award-winning

writer, cum laude graduate of Harvard, who shows what the future looks like. We have Barack Obama, who became the first Black

president of the United States. And Kamala

Harris, the first black female vice president of the U.S. African American

innovations, impacts all aspects of our lives. We eat the potato chips,

first created by George Crum in 1853; many of us have played with the Super

soaker invented by NASA scientist Lonnie G. Johnson. Mobile communications owe their beginning to

the 1887 invention of the telegraph by Granville T. Woods. Open heart

surgery, pioneered by Daniel Hale Williams in 1893, has saved millions of

lives, as those committed by Charles Drew and his invention of a technique to

preserve blood plasma. And even now, we are witnessing the miracle of a

covid vaccine thanks in part to the work done by Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett.

We do not wait or

expect freedom from legislation or judicial decrees. We are free by

virtue of being – humans. As we enjoy another Juneteenth, we shall

continue to persevere, serve, invent, and excel. By any means necessary, we will not only

continue to survive but also thrive and set new standards of achievement.

It is more than our right; it is our mandate from the Creator of all. We

will settle for full accountability and responsibility for past wrongs.

While we recognize that reparations are due, we have no confidence that any

will come soon. No, we will not take any

more promissory notes. We will, however, demand that schools and

courts, political institutions and economic systems, police and legislatures

act responsibly, equitably, and justly for us and our prosperity. To

guarantee these premises, we promise to do the following: litigate, assemble,

agitate, propagate, and instigate a continual revolutionary struggle. We

shall do more than overcome; we will more deliberately, meticulously, and

strategically utilize and maximize our voting, economies, and communities to

foster change and new realities.

Thank you…

Comments

Post a Comment