Lest we forget -yes, there are Black male stereotypes

"I am what time, circumstance, history, have

made of me, certainly, but I am also, much more than that. So are we all."

– James Baldwin

In a previous chapter, we argued that to destroy the

alliance forged between the Irish and African servants, the White planter class

created the myth of Whiteness and convinced the Irish that they were White.

Along with this myth came the presumption of privileges presumed to be associated

with being White. These myths of Whiteness and privilege continue to be

utilized, as seen in the most recent M.A.G.A. movement where poor Whites are

being urged to once again serve as the frontline troops for the White war

against Black, Brown, Indigenous, and Asians that would dare to presume equality.

What was not discussed, and the focus of this last section, is how this same

process created a whole slew of stereotypes purposefully aimed at the "Black

man." Fear of the Black man runs

deep, and the only real way devised by the White structure was to convince the Black

man that he, not the system, was the problem. The weapon used for this purpose

was the multiple ways his identity was manipulated to produce his worst nightmare.

Your

History II by James Pate. Charcoal

A search of the internet reveals a whole litany of words used to describe the black man. Some nicer words include: dim-witted, bumbling, lazy, angry, sexually aggressive, forsaken, sad, betrayed, suffering, unloved, and ridiculed. And the most virile would be ape, Coon, Jungle Bunny, Kaffir, monkey/porch monkey, zibabo, spade, spook, and of course nigger/nigga(h). Attached to these words would be such stereotypical characters as Zip Coon, Sambo, Jim Crow, Uncle Tom/Uncle Remus, and Buck/Mandingo. And for most of this same period, there has been a constant rejection of these images as Black men and women have fought for the very soul of our community. Tracing these stereotypes to their origins helps us understand how and why they came into being and how and in what ways Blacks continually recreated their identities. Our journey begins with Zip Coon.

Zip Coon -A.K.A. Slick

Who is he? They call him Slick

(Slick)

Restin' and a-dressin' and a-mackin' strong

Trying to find somebody to run a game on

Oh, they call him Slick (Slick)

Now Slick ain't got no regrets

Slick ain't got no sorrows

If he don't get you today

He'll get you tomorrow

And oh, they call him Slick (Slick)

He's full of tricks (Tricks)

Be your friend, oh, you bet ya (Hey baby, what's

happening?)

It all depends on how much Slick's gon' get from

you, yeah?

(Hey baby, let me holding something, I know you

got it)

Slick, Willie Hutch from the soundtrack

of the Mack (1973)

Slick's first incarnation predates the U.S., as Europeans first explored Africa and kidnapped young children, primarily boys, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. These children became much like pets, as the European elite dressed them in elaborate clothes, providing education and training to become "luxury" enslaved. As the British extended their control over the Americas, Blacks in fancy dress were presented as a form of slave luxury, often seen on exhibit at carnivals and cross-dressing festivals, and favored slave status. By the turn of the century and the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Dandy reemerged in Zoot Suit, top hats, and canes. (White and White 1978)

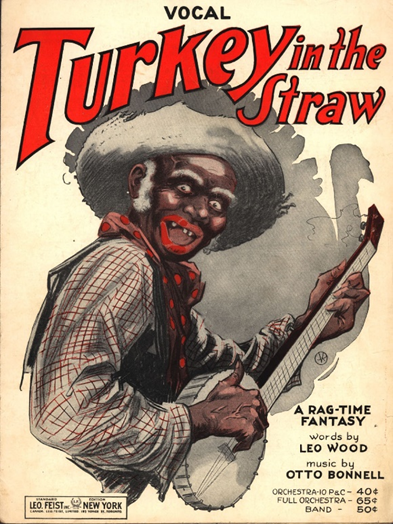

Zip coon, in the early Minstrel shows, was often represented in his "bright, loud, exaggerated clothes: swallow-tail coat with wide lapels, gaudy shirts, striped pants, spats, and top hat." Zip's days were spent sleeping, hunting, and shuffling along. The only time when he was not doing these things, he was stealing chickens or dancing. (Lemons 1977) Zip Coon first appearance was in 1934 and was popularized in minstrel shows. Later, the melody was used in the more popular song Turkey in the Straw, published in 1861. And then, in 1916, "turkey in the Strat" remerged as "Nigger Love a Watermelon, Ha! Ha! Ha! performed by Harry C. Browne and produced by Columbia Records. This final version served to become one of the most obvious racist themes within America. Strange, on many hot days, as the ice cream truck lumbered through neighborhoods in our country -few would connect the song being played to this song. You remember –"Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Moe." And no, it had nothing to do with 'catching a tiger by its toes". Next time that ice cream truck song comes along, remember where it originated. (Johnson 2014)

In 1973 "The Mack" debuted in the

blaxploitation genre. In this film, the lead character, during the civil rights

movement, opted to become a "Pimp" instead. (King

2013) The pimp is just the most recent incarnation of the "Black dandy"

known as Zip Coon. Here we see how the prejudice and fascination of the White

society have created a hypervisible, hypersexed, violent, and lawless Black

man. (Eshun

2016)

Historically, almost every Black man of note, from Frederick Douglass to W.E.B. DuBois, from Malcolm X to James Baldwin, could have been described as a dandy. Today, if one looks to the height of Black male fashions, they will again be greeted by the Dandy. (Gbadamosi 2016)

As we view these identities, we fail to understand that

Black men are active agents in creating their masculinities. And while none of

them, or us for that matter, are perfect, we should neither vilify nor romanticize

these identities. Black masculinities continually challenge the stereotypes as

they reimagine, reproduce, and realign their identities. Unfortunately, even during

these challenges, Black males have been subject to over-policing. Consider the

case of Trevon Martin, who was killed because he was wearing a hoodie and was presumed

to be a gang member. And the irony is that George Zimmerman was acquitted as

the all-White jury agreed with this assessment.

One of the strangest cases of misidentification was witnessed

when Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates was arrested as he attempted to enter

his Cambridge, Massachusetts, home by local police officers. (Pilkington

2009) Even having the wrong hairstyle

can cause police to overreact, as Clarence Evans learned. While playing with

his kids outside his own home, Evans was accosted and forced against his car by

a White deputy who mistook him for a suspect. Even after proving that Houston

Police had wrongly targeted him, the police officials and union "saw

nothing wrong with the encounter." (Miller

2019)

Strangely, as education and income go up, the

intersection of race and gender demonstrates that if you are White or a Black

woman, there is a reduced risk of discrimination and depression. However, the

opposite is true for Black men, who are targeted as "dangerous, threatening,

and inferior." Consequently, research demonstrates that these conditions

lead to an increased risk of depression among higher-status Black men (Assari, Lankarani, and

Caldwell, 2018) and boys (Assari and

Caldwell, 2017)

Being wealthy, or even one of only five Black republicans

in Congress reports being stopped no less than seven times in one year for

doing nothing wrong but driving a new car in the wrong neighborhood. (Vega

2016) A scary conclusion reached by

researchers reporting in the NYTimes reveals that Black boys, even from some of

the most affluent families and neighborhoods in America, still earn less in

adulthood than their white peers. More troubling is that Black boys from the

highest economic group are likelier to end up poor, while White boys from the

same tier are likelier to remain rich. (Badger,

Miller, Pearce, and Quealy, 2018)

More to come...

Comments

Post a Comment